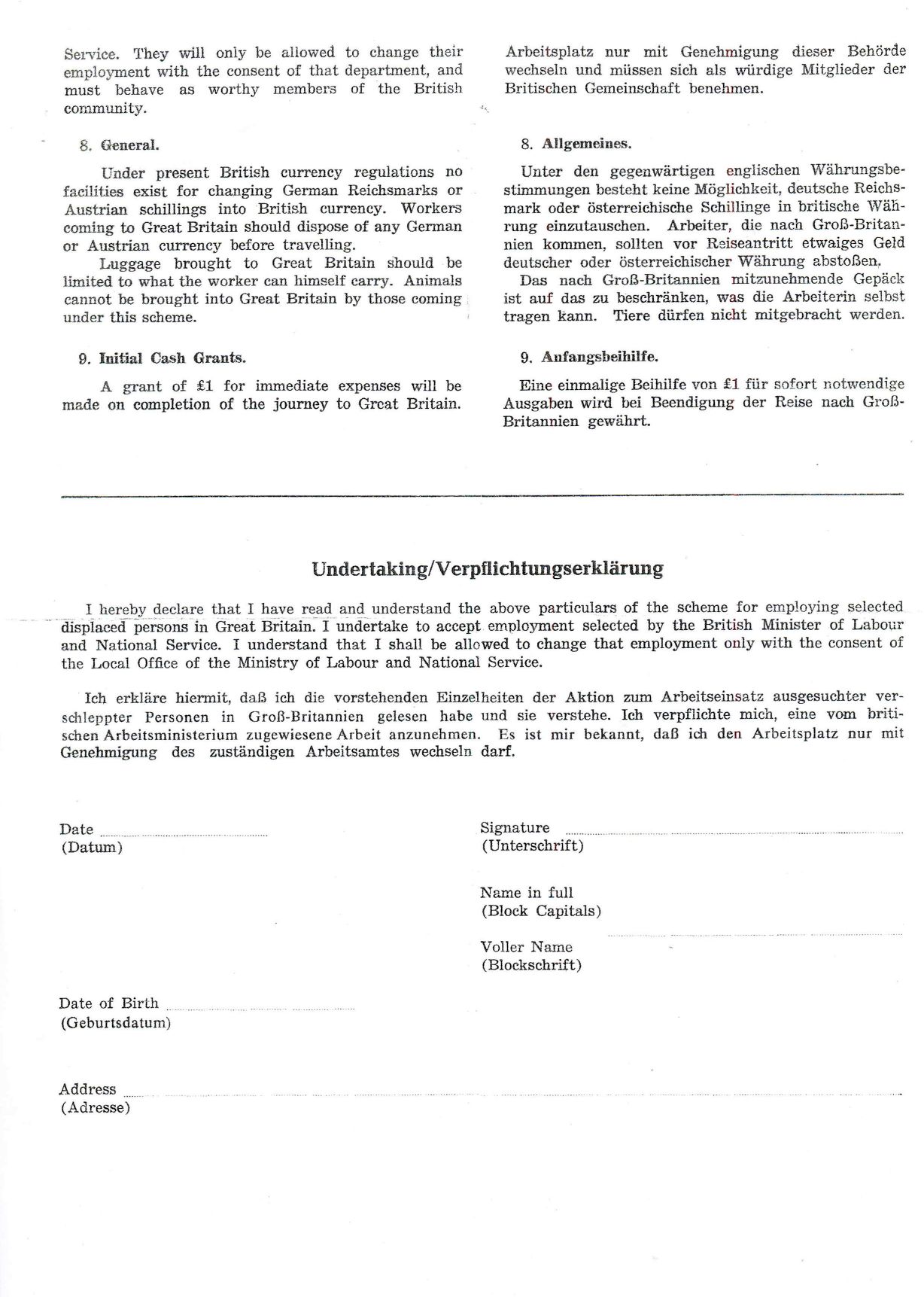

Great Britain was the first of the Allied authorities to introduce a scheme to help the Latvian Displaced Persons stranded in camps across West Germany. In the autumn of 1946, the British Government introduced a labour scheme called “Balt Cygnet”, which enabled Latvian (and Lithuanian and Estonian) DP women aged between 18 and 40 years old, to leave the DP camps, travel to Britain, gain employment and receive accommodation and wages. The first group of 100 women to join the scheme, left Lübeck DP camp on 16 October 1946. They travelled by boat across the North Sea and arrived in Tilbury, in the south of England, a few days later. They were then sent to tuberculosis (TB) sanatoria across Britain, where they worked as kitchen hands, ward maids, cleaners and laundry workers.

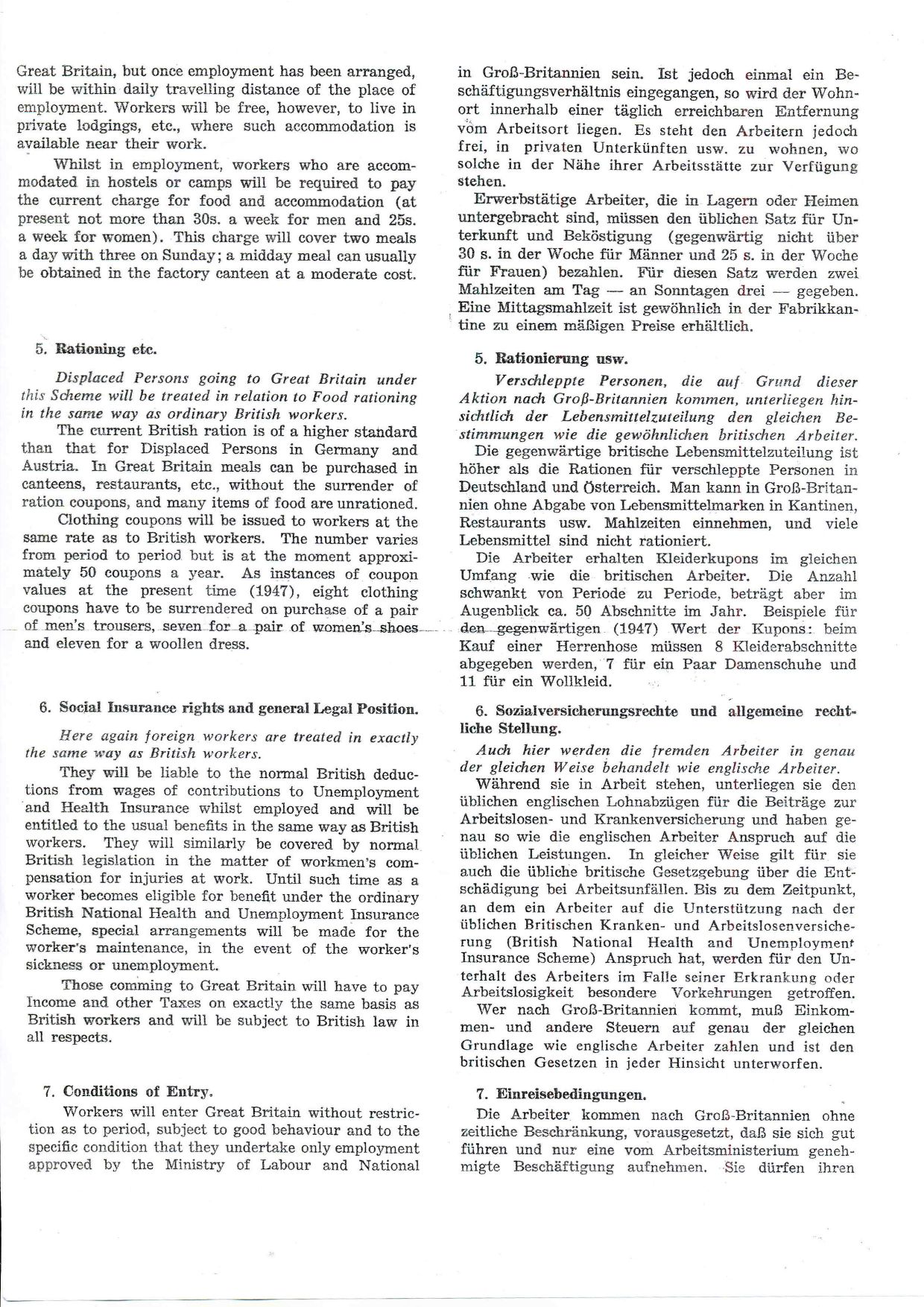

“Balt Cygnet” was known as a European Volunteer Worker or EVW Scheme, which along with “Westward Ho!” (introduced in 1947), brought over 14,000 Latvian Displaced Persons to Britain between 1946 and 1950. The British Government had two motivations for introducing the EVW schemes. The first was the need to reduce the huge cost of accommodating the DPs in camps in Germany, and to find a longer-term solution to the issue of the DPs, which also created complex political, social and humanitarian issues. The second reason for the introduction of the schemes, was severe labour shortages in Britain in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War. Post-war Britain was in a precarious state, its economy was on its knees and many industrial sectors had virtually collapsed as a result of war and manpower shortages. The numbers of men returning from war were insufficient to meet the labour demands of the economy, and women who had worked in wartime industries were no longer available, as they returned home to look after sick and injured husbands. Britain was over-reliant on imports especially of coal, and a significant injection of manpower was required to rebuild the British economy. Employment sectors such as hospitals and TB sanatoria were also in need of manpower, due to the huge numbers of unwell and injured returning soldiers and the unpopularity of these jobs to local people.

“Balt Cygnet” placed Baltic and later, Ukrainian, women in TB sanatoria and hospitals and proved immediately popular and successful. The scheme was quickly extended to include women who wanted to train as nurses and midwives, and women up to age 50. Towards the end of the scheme, recruitment was also extended beyond the British zone to the US zone of West Germany, and by May 1947, almost 2500 Latvian, Lithuanian, Estonian and Ukrainian women had arrived in Britain under the “Balt Cygnet” scheme. In all, 23 parties of about 100 women each, were sent to Britain via this scheme.

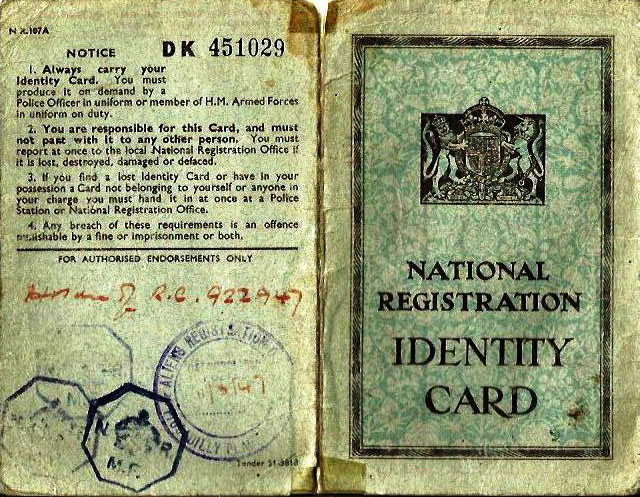

Upon arrival on Britain’s shores, the “Balt Cygnet” women, carrying little more than a small suitcase and a coat, were greeted by members of the Women’s Royal Voluntary Service, who gave them cups of tea and a hot meal, and advised them on plans for their onward travels. They were then taken to registration centres where they received further medical checks, money, clothes and instructions on their placements. The women were sent either individually, in pairs or small groups, to their work placements, and were accommodated either within the sanatorium/hospital grounds, or nearby in private lodgings. Most of them found it a nerve-wracking, but positive experience.

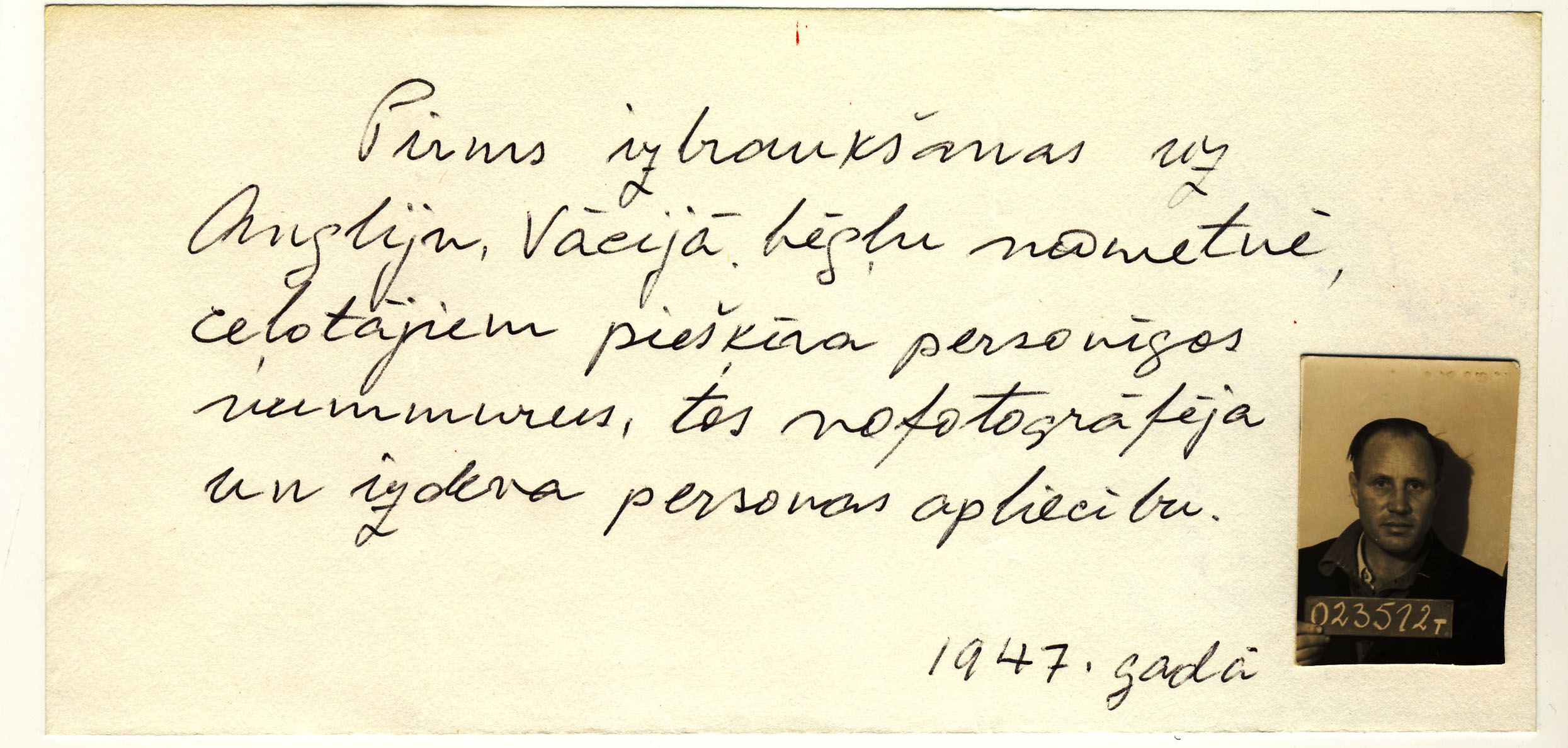

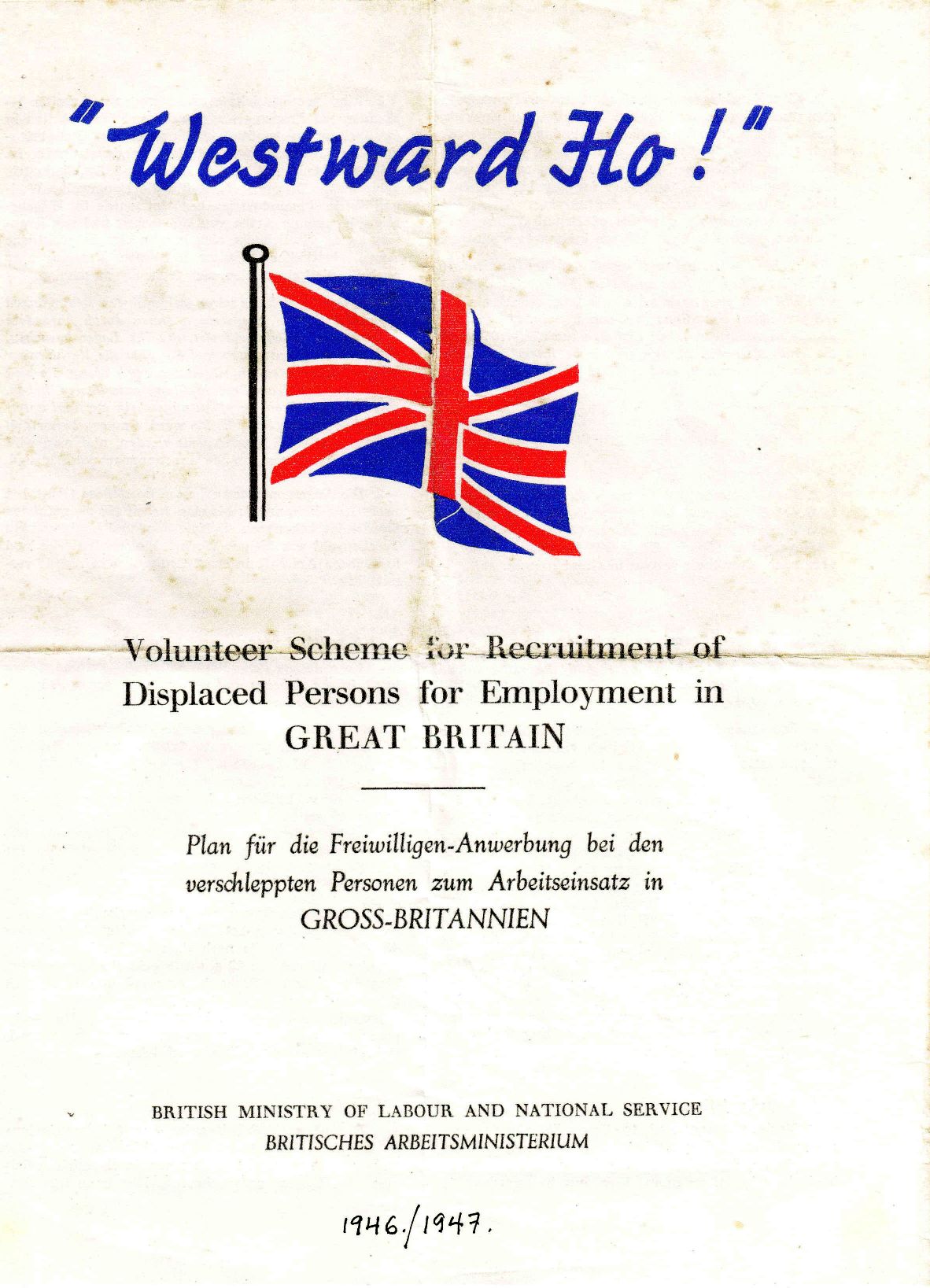

In 1947, due to the huge success of the “Balt Cygnet” Scheme, a second EVW scheme – “Westward Ho!” - was introduced. This was a much larger scheme, which recruited both men and women from the DP camps to work in a broader range of economic sectors in Britain, including agriculture, coalmining, textile factories, brickworks and forestry work. “Westward Ho!” also employed a wider variety of nationalities, but continued to prioritise Latvians, Lithuanians, Estonians and Ukrainians.

The first recruits to “Westward Ho!” arrived In Britain at the end of April 1947. In just one week, over 1000 recruits were brought to Britain via two ports – Tilbury in the South, and Hull in the Northeast of England. By the end of May, nearly 10,000 DPs had been brought to Britain under this scheme, of whom 42% were women, who continued to be recruited for work in hospitals, as well as for the textile industry. From the end of 1947, dependants of the EVW recruits were enabled to come to Britain to join their family members. By December 1950, the total number of Latvians who came to Britain as part of both “Balt Cygnet” and “Westward Ho!”, was 12,919, plus 1,322 dependants, totalling over 14,000.

The Latvians who came to Britain on the EVW schemes, were keen to leave the DP camps and begin a new life, given that return to the homeland was not possible at the time. Many of them were young adults keen to get on with their lives, begin careers, settle down and plan for their futures. They were attracted by the British Government’s promises and heard positive accounts from earlier recruits to the schemes. It was not an easy decision or an easy move. Many struggled hugely with being away from their families and homeland. The Latvian community set up structures and community groups as quickly as possible, to help the newcomers. The Latvian Welfare Fund (DVF) bought a property in London at Queensborough Terrace as its London hub, and began establishing groups around the country, while In 1950, the Latvian National Council in Great Britain was established at the suggestion of the Latvian Legation in London, as a representative body for Latvians in Britain. Latvian newspapers were circulated across the community, and cultural events and celebrations were also organised, replicating many of the activities in the DP Camps.

While some Latvians moved into private lodgings very quickly after arrival in Britain, others, especially those working in agriculture and forestry, stayed in hostels and temporary camps for many months, even years after arrival. Although conditions were variable, one of the more positive aspects of hostel and camp life, was that Latvians felt less isolated and were able to come together, plan and organise community and cultural events, and talk about the homeland, as well as have visits from Lutheran representatives. English classes were also organised in the hostels, camps and workplaces, but were not well attended. By 1950, many of the Latvian refugees were still hopeful that their stay in Britain was temporary, and that one day soon, they would be able to return to their beloved homeland of Latvia.

Source: Emily Gilbert (2017) Rebuilding Post-War Britain: Latvians, Lithuanians and Estonian refugees in Britain, 1946-1951, Barnsley: Pen and Sword.

Paulīne Mucenieks. OMF23001 – 42. 12.03.97.

Rita Vanags. OMF23001 – 42. 13.03.97.

Pauls Vanags. OMF23001 – 43. 13.03.97.

Reinis Gabaliņš. OMF23001 – 85. 12.10.97.

Laimonis Ceriņš. OMF23001 – 91. 19.10.97.

Gunārs Tamsons. OMF23001 – 47. 18.03.97.